Table of Contents

Surrender

A travelogue by Shelbatra Jashari

Blown by the wind

In the summer of 2012 I went on a very special trip. Not a speciality trip, not particularly a spicy trip… but one that I won't easily forget. The first goal of this journey was to document two case studies of the Resilients project: the Pollinators and the Unmanned RT. Both stops happened to be in the Balkans, and in the two weeks that intervened between them I decided to have an appointment with the land of my childhood, which was right in the neighbourhood – Kosovo, Kosova or Kosovë, depending on your orgins.

First stop is the island of Rab, Croatia. Croatia is the country where I happened to spend maybe eight out of twelve of my childhood summers, being a remnant child of the vanished country of Yugoslavia. While on the boat from Rijeka to Rab (the boat is full of drunk teenagers, and they ask me if I am Severina; come with us to Pataya to see Carl Cox, they suggest), the bora – the cold winter wind that seems like an omen of the apocalypse in the summer – catches up and chases me. Butterflies – or was it dragonflies? – were in my stomach in anticipation of the coming Resilients adventures.

In Rab we stay in a household with the Performing Pictures contingent of the Resilients team. It is an open-plan space where family and friends share sleeping quarters, a kitchen, and the sun. It is built out of very old stonework and has been in the family for several generations. In contrast to the tourist buildings around the coast – newly-built concrete and glass edifices devoid of history and empty of meaning – my hosts consciously make an effort to keep their family history alive by building on the family stones that have been around for at least a century.

The house has no electricity or hot water. I arrive after sunset, entering the dark interior at the end of my first day in the Balkan sun, and feel like I’m stepping into another time. We have dinner on the floor. I’ve only been gone from Brussels 24 hours and I can already feel a transformation. A week without a warm shower or electricity in foresight, and with no light at night. I was not entirely prepared for this, but these new challenges help to forget the bora and plunge into the organisation of every day as it comes. In the company of the mistress of the house, a journeyman and his lady, a tattooed Croatian sculptor, and the kids (one of them apparently escaped from a comic book), I call this place home for the next week.

We are awaiting the arrival of the Peregrini/Pollinators – but the bora has delayed them. This group of artist-journeyers has been biking their way across half of Europe from Poland to Rab in an epic “karma biking” adventure, a pilgrimage and experiment in resilient modes of cultural transport. I interviewed the participants once they arrived in Rab, listening to their multifaceted and often passionate tales.

Meandering in the open air, showered by falling stars

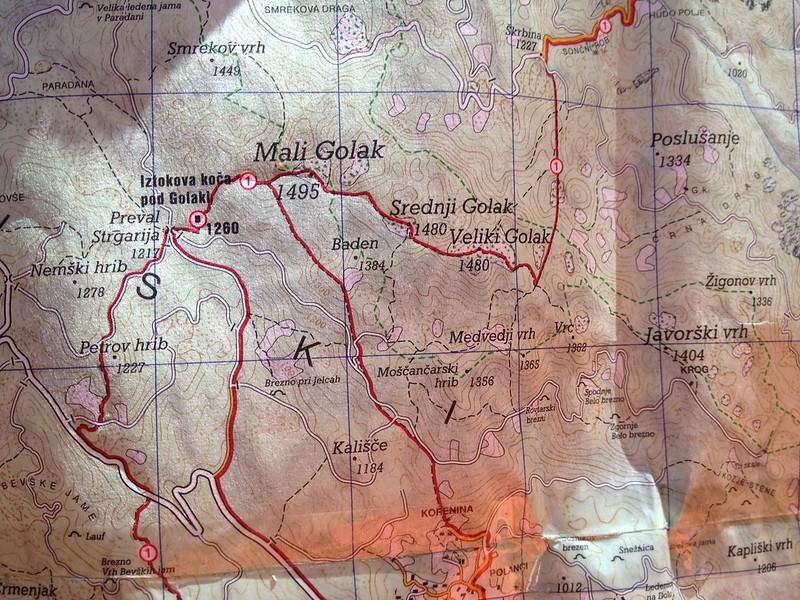

A few weeks later, a few hundred kilometers away… Time to step onto another planet: the Unmanned Resilience hike. We are hiking up Route 1 into the Gora mountains in Slovenia with a bunch of artists, pilots, navigators, unmanned flying vehicles, and SiNuNi data collectors. Our hosts welcome us in a mountain house – with limited water and no room for sleeping inside. Sleeping under the stars awakens my romantic feelings. It makes me happy and my body stiff, but I can make wishes throughout the night to the endless falling stars. Next morning we meet our guide, expert in wild herbs and Slovenian punk and hardcore enthusiast[He's still playing in two punk/rock bands, one (Bretones) doing traditional breton music Ramones style and the other (Crazed Farmers)], the legendary Dario Cortese…

Dario changes your perception of the world. A collage of contradictions and a wise mountain guide, he leads us through the wild, helps us tell the good herbs from the bad, advises us on resilient food and drink and regales us with tales, songs and reflections on wild garlic, ticks, and sleeping. (He convinced me that your legs should always be higher than your head when you sleep – this was supposed to have some kind of beneficial effect on longevity.) During nights in the open the sounds of stars and wild animals are a background to the hilarious soundtrack of the snoring group. It is so conforting to find a home in meandering and the open air.

I encounter Kenny and Hafiz on my way back from doing some hanging exercises in the mountain trees. Their arrival is a sign that we're nearing “civilisation” again, as they take out their computers ASAP and start debugging the SiNuNi, their weather and land recording device. The SiNuNi collects data from sensors, stories from people and locations from a GPS. With the entire hiking group we find our way to the first mountain hut after two days of travelling. There we find real food and drinks.

Are there any goats in the Gora mountains – and if so, where are they hiding? Back in “civilisation,” the most memorable moments for me are ATOL pilots’ drone tests on the first night. The drones had a sci-fi ninja triangle shape that made me think of a Daft-Punkish anime. They flew over the region of our hike during the night and sent detailed images back to us. The next day we sat down and tried to spot the goats in the aerial photos. They were nowhere to be found. In desperation, some of us started Photoshopping the goats into the images; others started seeing dragons and lots of other creatures in a hallucinating pixelfest. But the mystery remained – where did all the mountain goats go? We asked ourselves if it was due to the weather, or if they’d all been eaten by the wild bear that was at large (and also stalking us). Our speculations became more and more improbable and crazy – but we never solved the mystery.

Green landscapes beyond the grey rocks and a purple sunrise

Between my two scheduled Resilients odysseys, I had an appointment with karma in Kosovo. I called it my personal pilgrimage of love – a transformative journey to my homeland. I dived south along the Croatian coast and onward to Kosovo and Albania, and finally visited my own model of resilience – my grandmother.

I board the Liburnija, the ship from Rijeka to Split, and sleep on deck under the stars, contemplating the many possibilities of a boat as a platform for being playful. The ship’s bar hosts a strange assortment of characters. All the bartenders are tall, have moustaches, and wear black and white suits. They look like they escaped from a communist jazz band from the times when Yugoslavia still existed. An inconspicuous picture on the wall of the Pope, who had once travelled on this same vessel.

Arriving in Split to a purple sunrise, the colours of the city blow my mind. Torn posters on the pavement seem to be inviting me to a “Broken Hearts Club”… No time for that, rather a look at this old port town; palm trees, royalty, old Balkan Illyrian connections, mysterious encounters, ancient architecture and stonework. Every morning the whole city, it seems, comes out to bathe in the sea.

Leaving Split I embark on a 20-hour bus ride that takes me further and further into the “wild east.” The rocky grey Croatian coast, the Bosnian town of Neum and then into the dark of Montenegro – the black mountain where green (painful to the eyes) starts colouring my landscape. We must wait hours for passport control at each border between these countries. I get off after dark in the coastal town of Ulcinj, against the advice of the bus driver, who on discovering that we both speak Albanian says it’s not safe for a lady here at night and urges me to catch a taxi onwards to Kosovo. But I end up waiting here nonetheless, on the closed “Little Beach” of Ulcinj, and sleep away the remaining eight hours on the 200 km bus ride to Kosovo without mishap.

Time’s might have changed in the Balkans… and so have ladies.

Journeying inwards, from endurance to acceptance

Kosovo defies my expectations every time I return. I love hearing my mother tongue en masse, can't really explain why. This is always my first strong impression – that and the heat that is a blessing. Funny to notice how my way of speaking has a tendency to change after two weeks in the Balkans. Often I hear that I say “please” and “thank you” too much. Its a source of amusing irritation.

I arrive during a time when the whole country is fasting: it’s Ramadan. I decide to try out this form of religious penance as a part of my exploration of spiritual practices of endurance. Unfortunately my efforts are misinterpreted and seen as a fake pose emerging from my own weirdness. Instead of Ramadan I launch into performatic overdrive, climbing pole-shaped objects every day and continuing my hanging series. 1)

I have won in my surrender to the law of the worlds. I surrender to simple happiness, becoming part of my environment wherever I go. I have won over belonging and unbelonging. I accept my alienation.

On a playground of ghost creatures

I encounter a group of young creators working on the project Prishtinë – mon amour. One of them is Astrit Ismaili, an emerging artist from Prishtina working on the re-appropriation of traditional Albanian tools – post-primitive body extensions inspired by the traditional Kanac from Hasi that was used as transport and carrier for women harvesting their fruits.

Another is Liburn Jupolli, a sound artist doing weird experiments with old instruments and re-appropriating them into sound-sculptures. These young artists welcome me and show me round the building where I have so many memories – a place called Boro and Ramiz, the Prishtina symbol for the Yugoslavian connection between the different Kosovar populations. (Serbian Boro and Kosovar-Albanian Ramiz were World War II comrades who died in battle together, becoming a symbol of brotherly partisan friendship.)

Since the last Kosovar-Serbian war the building has served as a parking lot, but Prishtinë – mon amour have re-appropriated the space as a venue for sweet performances that refer to a Sonic Youth-ish universe at its best. Some girls are putting up stickers on traffic lights and walls with the motto, “never stop loving.” Finding this in the city where I was born is like discovering a treasure on my pilgrimage of love. I determine to never stop loving, no matter how close to despair.

Further down south on the beaches of Albania, the bora wind catches up with me again, showing me the cold, loveless face of the universe once more. In this wind it’s not difficult to imagine the beach as a playground for ghost creatures. I can't hide anymore under the umbrella, they're all closed, the wind is too strong…

link to the video

Berat is one of the oldest inhabited castles in the Balkans and one of the best-preserved Ottoman architectural constructions. The white city, the city of myth, the city of stone. Albania carries myths of stone over from century to century, as if they were newborn babies. Stone is what is worshipped in traditional albanian culture. Expressions like: he's strong as a stone, your head is a stone… and the myth of Rozafa, the woman that gets buried alive in the walls of her husband’s castle so that it may keep standing. In Albanian culture we strongly believe that only a sacrifice of life can keep a construction solid for eternity. So living being were sometimes buried alive to keep a construction standing and to free it from bad spirits.

Descending to my roots, I climb and hang on…

Getting lost in order to find myself again I make an effort to reconnect with my roots… and also take the opportunity to explore possibilities for climbing and hanging – reminding myself that my determination to hang on is the only thing that really matters.

Before heading back to the West I pay tribute to my ancestors. I go up the mountains to honour the Catholic cemeteries in the town of Zym. On the way I come across “Neptune,” a strange and remote cafe that consists of little more than a concrete platform where coffee, food and drinks are served. This could be the perfect place for a performance. It couldn’t get more grey, more concrete, more alien. The space: a backdrop to some Shakespearian play ending in suicides…

At the end of my trip I make time to visit my grandmother – a personal, enduring symbol of resilience for me. A 95-year-old optimist, she lives in the same village where she married 78 years ago. Her daily yoga consists of the traditional Muslim prayers to Allah five times a day, which she practices in her own very unique way. She fascinates me – the rich simplicity of her life. She is my mastodon and I offer my prayers to her.

Leaving her behind makes me recall all the goodbyes I’ve said up to now. Surely too many for a lifetime.