Table of Contents

Borrowed Scenery: Cultivating an Alternate Reality

by FoAM

In the Japanese text Records of Garden Making (作庭記, Sakuteiki)1) attributed to Tachibana Toshitsuna (橘俊綱, 1028–1094 CE), the concept of 'borrowed scenery' (shakkei in Japanese, jiejing in Chinese) was first introduced as an approach to designing gardens. It is presented as a way of including features from beyond the garden as elements in the design. Distant mountains or rivers, clouds, rocks and even stars can be incorporated. Although the garden and the surrounding landscape may be topographically separate, 'borrowing' or 'lending' provides a way to experience them as one whole.

Inspired by shakkei and jiejing gardens, FoAM developed the alternate reality narrative Borrowed Scenery, a story without a narrator or explicit narration which unfolded through hints, suggestions and immersive ambiance. By 'borrowing' from sources as diverse as plant mythology, patabotany, Tarot, plant sciences, historical mysteries and the setting of the everyday, Borrowed Scenery became a place to experience an alternate reality (past, future or parallel) where plants are a central aspect of human society.

Borrowing has an ambiguous reputation in the arts. The twentieth century has seen much redrawing of the lines between influence, copying, reference, theft, public knowledge and common heritage. Some artists borrowing directly from copyrighted books, music or proprietary software have been severely punished. On the other hand, remix culture and the free software movement are intrinsically founded on borrowing and re-appropriating from a shared cultural commons. Not only does borrowing create new works; these works – including Borrowed Scenery – would simply not exist without it.

In an alternate reality narrative (ARN), borrowing from 'consensus reality' becomes a way to draw the audience into the story. The familiar reality of popular culture acts as a bridge between life and fiction. What emerges is a storyworld – a web of experiences, tales and conversations between ARN creators, real visitors and fictional characters. Borrowing in an ARN is like leaving a trail of breadcrumbs from the 'consensus' to the 'alternate' reality. It is about establishing familiarity and intimacy with visitors through personal associations, memories and opinions, making their plunge into the storyworld a less alienating experience.

Whispering a world into being

The term 'alternate reality' may require some elaboration. We borrowed this term from alternate reality games (ARGs).2) In Borrowed Scenery we focused less on the gaming aspect of ARGs and more on the creation of a storyworld with hints that it could become real. We allude here to some of the more esoteric traditions of storytelling: invocation, divination and sympathetic magic.3) We attempted to use stories to 'will a reality into existence'. We did this by creating events and characters that were based on real people, reacting to real occurrences by incorporating new story elements on the fly, using the physical space of the narrative as a real-life lab. What would begin as a story could become part of daily life. Perhaps someone would cook more vegetarian dishes, or spread edible plants in cities, while others might adapt their working rhythms to the seasonal daylight. In this way the alternate reality of Borrowed Scenery would echo through consensus reality long after the project was over.

Borrowed Scenery was balanced on the creative tension between story and reality. In real time, the ARN evolved over two months during 2012, but the story was set in an ambiguous 'smeared now' suspended somewhere between the early nineteenth and late twenty-first centuries, imbibing touches of art nouveau, steam- and biopunk. While there was a backstory that tied disparate elements of the project together, it was rarely narrated explicitly. It was visible as small fragments and subtle hints, such as a label on a herb jar or a half-written letter. We relied on the immersive ambience of physical space to encourage visitors to piece together the territory of the storyworld. The experience was designed to be more like travelling to a foreign land than watching a movie. More about sense-making than storytelling.

Experiencing and recounting

Narrative has always been about a mix of invention and repetition; we seem to like stories because they follow the rules we've learned to recognise, but the stories that we most love are ones that surprise us in some way, that break rules in the telling. They are a mix of the familiar and the strange: too much of the former, and they seem stale, formulaic; too much of the latter, and they cease to be stories.

– Steven Johnson4)

While making Borrowed Scenery we often deliberated on the differences between stories and reality. A reality literally encompasses places, events and people, while a story is always an account of events, places and people. An alternate reality narrative should attempt to draw both of these together – actual people and events that can be encountered in their immediacy, entwined with experiential traces of the fictional characters and their lives. As Borrowed Scenery was also a physical narrative, these traces were contained not just in words and media, but also in physical objects, furniture, plants and spaces. With so many 'story containers' and possible paths and associations between them, there was no final way to 'tell' a coherent story. Our task was to design a framework within which the alternate reality could exist – first as a backstory, then as a collection of story-fragments embodied by physical objects and digital media mixed with live events and real people. As in consensus reality where each of us lives in our own reality tunnel,5) it wasn't possible for anyone to experience the ARN in its totality. Instead of attempting to create a master narrative with a beginning and ending, it became more important to think about Borrowed Scenery as a complex and immersive 'reality', a storyworld. People approached and engaged with this storyworld in different ways. Although necessarily an oversimplification, we noticed that there were three distinct ways that visitors approached this storyworld: as performance, consumption and interpretation. Some would move between all three in one session, others would come back a few times and try out different things. By observing how people explored Borrowed Scenery, we learned that it is beneficial to provide many possible ways to enter and explore an ARN.

Firstly, the most direct experience of Borrowed Scenery was simply being in the space and soaking up the atmosphere. We were pleasantly surprised how many of our visitors would do just that and need nothing else. Some reported states akin to natural mystical experiences.6) After a while they would emerge and talk to us about what happened, often grasping the essence of our backstory and the plant-inspired reality we wanted to evoke. Visitors inhabited the alternate reality, becoming protagonists without realising it. Some visitors would participate in events without engaging in the larger narrative, and even remained unaware of its existence. People would take part in a walk where they learned to forage for edible plants in cities, for example. On the walk their paths would cross with the fictional, their traces might be collected in the patabotanists' field guide, but they might remain unaware of this bigger picture. If they were interested in digging deeper there were several avenues they could explore, but if not, that was fine too. Sometimes we would hint at the existence of a larger reality by giving out small instruction cards, as invitations to explore further. The common characteristic of these disparate experiences (from meditative presence, to engaged participation and individual exploration) was a direct engagement with people and events, an improvisation or performance without a fixed scenario. As such it was closer to a reality than to a narrative.

Secondly, participants could experience Borrowed Scenery in a way that came closer to conventional 'story consumption' in books, movies or games: something like a treasure hunt for narrative fragments. This story-seeking became a quest to find a narrative that is dispersed through the environment, objects, events and media. For this experience to work there needs to be a high density of story fragments – every object and event should become meaningful within the context of the overarching narrative. This is quite time-consuming for the designers, but it requires the least commitment and effort from the audiences. They can experience a representation of the alternate reality that they 'dig out' from a collection of materials and media. The story – whether they find it or not – remains static. In Borrowed Scenery the story wasn't as linear as in a conventional treasure hunt or a Disney ride, so visitors didn't need to discover all the story-fragments for their experience to make sense. If they found the hints and were keen to puzzle together a narrative, this could enrich their experience, but it wasn't absolutely necessary.

Thirdly, 'story making' was an approach that could be seen as a middle way between story and reality. This is where visitors created their own stories based on their perceptions of the space, people and events. In Borrowed Scenery it seemed to be quite rewarding for people to construct their own versions of the story and weave the disparate elements into new narratives. They would often incorporate elements of the backstory without explicitly knowing of it. It was thrilling for us to hear our story told in someone else's words. Even more inspiring were the new stories that emerged, built on our invisible scaffolding.

A glimpse behind the story, or how to practice patabotany in a candy store

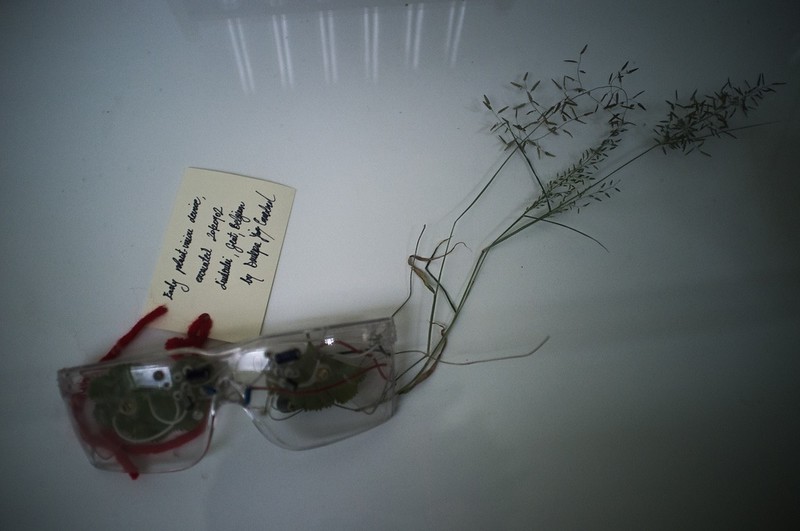

Borrowed Scenery spanned physical and online worlds, evolving over the autumn months of 2012. We converted the Snoepwinkel (Dutch for candy store) of the cultural centre Vooruit in Ghent into a physical narrative. The Snoepwinkel became a makeshift laboratory and living space at the centre of a storyworld populated by a team elusive patabotanists7) engaged in establishing channels of communication between plants and humans.

The patabotanists came from a place where both plants and humans are open to inter-species communication. They were fascinated by the apparent separation between the human and the vegetal in our reality and found it difficult understand how we hoped to survive in a world rife with social and environmental turbulence without closely collaborating with plants. They assembled a small team including an engineer, a lawyer, an alchemist, a cook and a linguist, led by the principal patabotanist, Alchemilla Lily Umiliata, and set off on their expedition to Ghent.

When the patabotanists began their work, they realised that the communication protocols common in their reality were not understood in this one, and they were met by a wall of silence from both plants and humans. After a period of bamboozlement and moments of despair, they came up with a three-pronged strategy. Some of them set off to find susceptible humans whose lives were already entangled with plants. Others worked on creating atmospheres where people could experience what it felt like to be a plant. At the same time, all of them worked on opening communication channels between carefully selected plants and humans. One of their experiments involved connecting plants to human brainwaves. Another was telling stories to plants in the hope they would eventually incorporate myths and cultural metaphors in their growth and form. And then there were others…8)

Realising that direct contact with human beings in our reality tended to be counterproductive, the patabotanists employed research assistants – FoAM's members and guests – to involve unsuspecting visitors, take care of plants, conduct field work and act as translators of the liminal story threads scattered through physical and digital spaces. Most of all, the task of the research assistants was to encourage visitors to see urban plant life with fresh eyes and re-imagine their cities as places of sinuous interaction between humans and plants. Although there was much interest in meeting the patabotanists, they could only be known through traces left in notebooks, schedules, pieces of clothing and tools, forum posts, messages and experiments in progress.

This blend of absurdist fiction and (pseudo/proto)science with real people and events was at times surprisingly smooth, other times overwhelmingly confusing, but people would rarely leave untouched.

Tending to the storytellers, weeding the storyworld

Visitors would roam through the space and piece together their own version of the story from hints and shards left for them to discover. People were eager to begin spinning their own tales. We served tea and let them talk. They would grab onto something that would remind them of their own relationship with plants and the story would begin. Sometimes they talked about personal experiences, other times we had heated discussions about the scientific validity of plant communication, or dreamed about a greener and gentler future. Some people would sit or lie down for lengthy periods of time, just absorbing the ambience. The original narrative, with its characters and their convoluted experiments, became a backdrop, a fertile compost for visitors' own story-making. Without us explicitly mentioning our references and inspirations – the Voynich Manuscript,9) McKenna's 'Plan-Plant-Planet' essay,10) Hildegard von Bingen,11) plant neurobiology12) or pataphysics13) – they were often quoted back to us, woven into the stories the visitors devised to make sense of what they experienced in the Snoepwinkel. In a way we also began borrowing from the visitors themselves – their memories, associations, storytelling abilities and even their presence itself.

These were some of the most rewarding and precious moments in Borrowed Scenery, alongside hours spent in the Snoepwinkel imagining what one or another character might be doing, adding traces of their activities and personalities in physical objects, writings, cabling and whatever else seemed necessary to enhance the atmosphere.

Creating the physical narrative was like gardening – cultivating a storyworld out of a wilderness of stuff and references. Whenever we were present at the Snoepwinkel, maintenance was the order of the day – cleaning, watering plants or checking experiments. These essential tasks took a significant amount of time and effort, similar to weeding in a garden. The moment we left them undone, the room would begin literally decaying and descending into chaos. One of the lessons we learned was that a physical narrative needs a full-time 'gardener', unless gathering dust and mess has a purpose in the development of the plot.

Aside from inviting people to the patabotanists' lab, we borrowed from the urban and online spaces where plants and humans interact. We began with a picnic14) in the Citadelpark where we asked visitors to partake in an experiment involving the ingestion or smelling of plant substances to accentuate or alter their experience. We were present at a community market, celebrating the beginning of autumn with a Harvest Fest, where we exchanged plant preserving techniques, recipes and produce. For two months we took visitors on walks to discover urban flora on the streets of Ghent: edible and medicinal plants, historic trees and other noteworthy vegetation. We mapped these walks and the plants using Zizim, a mobile app for urban foragers, and translated them into Aniziz, an online game where plants could come in contact with the patabotanists.15) We met 'Ghent plant people' (farmers, gardeners, city ecologists and other plant connoisseurs)16) and listened to their stories. Finally, on the day the clocks changed to winter time, we descended into the warm greenhouses of Ghent University's botanic gardens where we sang to and with plants in the language of Hildegard von Bingen's plant-infested Lingua Ignota.17)

'In bringing the spiritual and the material together in her Lingua, she invoked what the Russian formalists called ostranenie – making the familiar strange, or rather making the things of this world divine again through the alterity of new signs. In this sense it is a product of her Viriditas – greenness – making moist and green what threatens to become corrupted, mendacious, ill-used and dried out, but it is also a product of her keen interest in divine structure: The Tower reassembled.' – Sarah Highley

All of these disparate activities were episodes in the larger narrative, all sharing the same backstory. Each of them could be experienced on their own, which most people did. However, some of our visitors began treating the space and the story as their own: one of them decided to have a birthday party in the Snoepwinkel, as he felt the space reflected the world in which he'd like to live. Another visitor congratulated us on our Inner Garden performance, where she found that the plants sang beautifully. We all laughed when we realised that she actually missed the performance, but interpreted our story as an invitation to come and hear the plants sing, which made complete sense in the context of Borrowed Scenery. These people became integral parts of the narrative, where we merely provided the shell in which their fantastic stories developed.

Future borrowings

In view of the complexity, unpredictability and variability inherent at all stages of producing an ARN, we designed Borrowed Scenery with redundancy and layering in mind, ensuring that the project could succeed in a wide variety of conditions.

Crucially, we developed the ARN in multiple iterations, asking ourselves what the simplest and most basic form would be that the project could take while still retaining its essence. The essence of Borrowed Scenery was its immersive atmosphere that built on and subtly transformed the places we encountered. From there we could determine the optional and to some extent interchangeable extra details. We began with a small ARN that could be made reasonably easily relying solely on FoAM's own resources. This consisted of the rudimentary physical narrative: the space, minimal furniture, a soundtrack (and equipment to play it), printed maps and instruction cards, tea and tea cups, chalk, tape, sheets of paper, markers, a whole lot of plants and one FoAM member to act as the 'research assistant in residence'.

Having secured the project's 'bare essentials', we began to embellish them with additional elements that we felt would enhance the storyworld. In most cases we managed to ensure that digital components in the design always had an analogue backup (given the computer's infamous track record of malfunctioning the moment we rely on it in these experimental situations) and that there were several analogue layers. if the computer, internet, mobile phone or app failed, we had pens, paper, and printouts of maps handy; if an interactive mobile guide wasn't developed on time, we could give visitors printed instruction cards so they could still go through the physical experience.

Another example of design redundancy involves ensuring a multiplicity of possible experiences and points of entry into the 'user journeys',18) episodic events, and the ARN as a continuum. We wanted to accommodate a broad spectrum of possible engagements. For example, some visitors might be interested in learning how to preserve plant essences for entirely pragmatic purposes, such making their own jams or sauerkraut. These people could come to the Harvest Fest, enjoy themselves, learn and eat a lot, but remain oblivious to the larger narrative (even though certain characters and other hints were woven into the event). For these people each of the events and activities needed to be self-contained and meaningful in its own right. At the other end of the spectrum were those who wanted to know and become involved in everything, to the point that they began to merge into the ARN itself. For them the physical and online spaces had to keep evolving and responding to their presence and interaction, and there had to be a conceptual and phenomenological continuity between all the elements of the ARN. For these people it was beneficial to have the story appear at the 'acupuncture points' of their experience – as hints and suggestions that would draw them deeper into the storyworld.

With such redundancy built into Borrowed Scenery, we knew that no one would be able to experience everything, but also that most people would find something that interested them. Here we return to the idea of designing Borrowed Scenery more as a 'reality' then a 'story'. In the Ghent version of Borrowed Scenery, the physical aspects of the ARN were more appreciated than the online parts. People spent a lot of time in the Snoepwinkel, there was quite some interest in the events and the gifts (instruction cards, plant preserves, tea, maps…) were received with pleasure. Personal contact between FoAM's 'research assistants' and individuals or small groups was enjoyable for everyone involved and encouraged visitors' explorations and story-making. For the future we'd like to look deeper into ways that encourage meaningful story-making and sharing – by involving audience members more directly in the creation of the backstory, for example. A promising avenue for experiments in participatory storytelling is scenario planning (a technique derived from forecasting used to visualise possible futures) connected to improvisation and live-action role playing games (LARPs).19)

We found that, in contrast to the physical narrative, the online components of the project that focused on storytelling and gameplay receded into the background and at times were almost invisible. However, we do think it is worth persevering in finding ways to connect physical narratives with online environments, as it can bring together unlikely audiences, such as gamers and gardeners. It can also encourage participants to become more involved in the stories. Most of all, we remain curious to explore the magic of online traces becoming physical and tangible objects that extend their life in digital realms. To that end, the Borrowed Scenery website20) remains online for explorations and extensions.

Borrowing principles

We began designing Borrowed Scenery following the principles of Japanese gardening,21) and came to find that these principles could also apply to the design of alternate reality narratives. Loosely translated into ARN lingo, the principles can be summarised in four points:

- create ARNs to appear real yet strangely familiar

- ARNs should be site-specific and take advantage of the specifics of the site

- allow for gaps and imperfections as openings for new stories

- capture and share the atmosphere in such a way that it may, one day, become transformed from a story into reality.

Borrowed Scenery with its visceral connections to gardens and plants was eerily familiar. It was site-specific, designed for the Snoepwinkel and the streets of Ghent with online portals to other realms. The story was – for both practical and conceptual reasons – filled with gaps that encouraged associations and 'joining the dots'. Its intention was to become a reality. Even though as an ARN it existed for a brief moment in time, its seeds continue growing through consensus reality in unexpected ways: Zizim became a scientific app used to map lobster populations in the UK and a way to track urban agriculture initiatives in Ghent; Arboreal Identity has been translated into a guided nature walk in Brussels; the patabotanist archetypes are being translated into ethnobotanical Tarot cards; Inner Garden will be performed in other botanic gardens, spreading Lingua Ignota and patabotanical ideas further. Slowly, imperceptibly, the alternate keeps seeping into the everyday. Is it still a story or did it become reality? In the end, we might not be able to tell the difference. As in shakkei gardens, the ARN starts from ourselves, includes the cultivated frame of the storyworld and extends into untamed, infinite realities – consensus or otherwise.

Related

- Borrowed Scenery ARN: Borrowed Scenery credits and related notes

- Borrowed Scenery is a part of the European project PARN (Physical and Alternate Reality Narratives)